Deep Dive into FLBS: Honoring a Legacy of Learning

I have a condition. I don’t know what it’s called, or when it first emerged in my life, but I have noticed that it seems to rear its ugly head when I’m starting something new. The specifics of the something new don’t really matter. It could be a new community that I’ve moved into, a new job that I’ve started, or a new group of people that my wife has reluctantly allowed me to engage under the precaution: “Please don’t do anything embarrassing this time, Ian. I have to work with these people and we will not be moving to new town twice in one year.”

The onset of this condition runs like clockwork. It begins with a bizarre stirring of butterflies in my chest. Soon after, there’s an overenthusiastic burst of inspiration in my mind. And then, before I can do anything to stop them, words begin pouring out of my mouth, assembling—often to my own horror—into overly elaborate ideas of how I, in all my uninformed brilliance, can easily solve all of the challenges facing my new compatriot/employer/hometown before the day is through.

The worst part of this condition is not that these ideas are almost always naïve, or that I’m all but guaranteed to use at least seven terms incorrectly during my pitch. The worst part, which makes this condition truly humiliating, is my arrogant obliviousness to the fact that the people upon which I’m bombarding my ideas have already considered and determined them to be off target or not useful at all.

Now, I’m not saying that all of my ideas are misses. A few of my pitches have landed over the years, and an even smaller number actually made a difference for the better (such as this column, I’m sure you’re thinking to yourself right now). But innovation cannot happen without understanding, and true understanding can only take place if the more experienced have the willingness to teach, and the less experienced have the humility to learn.

In the early 1900s, when University of Montana scientists were first exploring and conducting research at the Flathead Lake Biological Station, they probably had plenty of hypotheses and predictions about the vast and breathtaking Crown of the Continent. However, despite their academic training and credentials, they had very little practical knowledge of the indigenous plants and animals of Northwest Montana. To get them up to speed, they would need to rely on the expertise and educational generosity of the Native Americans who were living in the Flathead Watershed long before any University of Montana researcher first stepped on Flathead Lake’s shores.

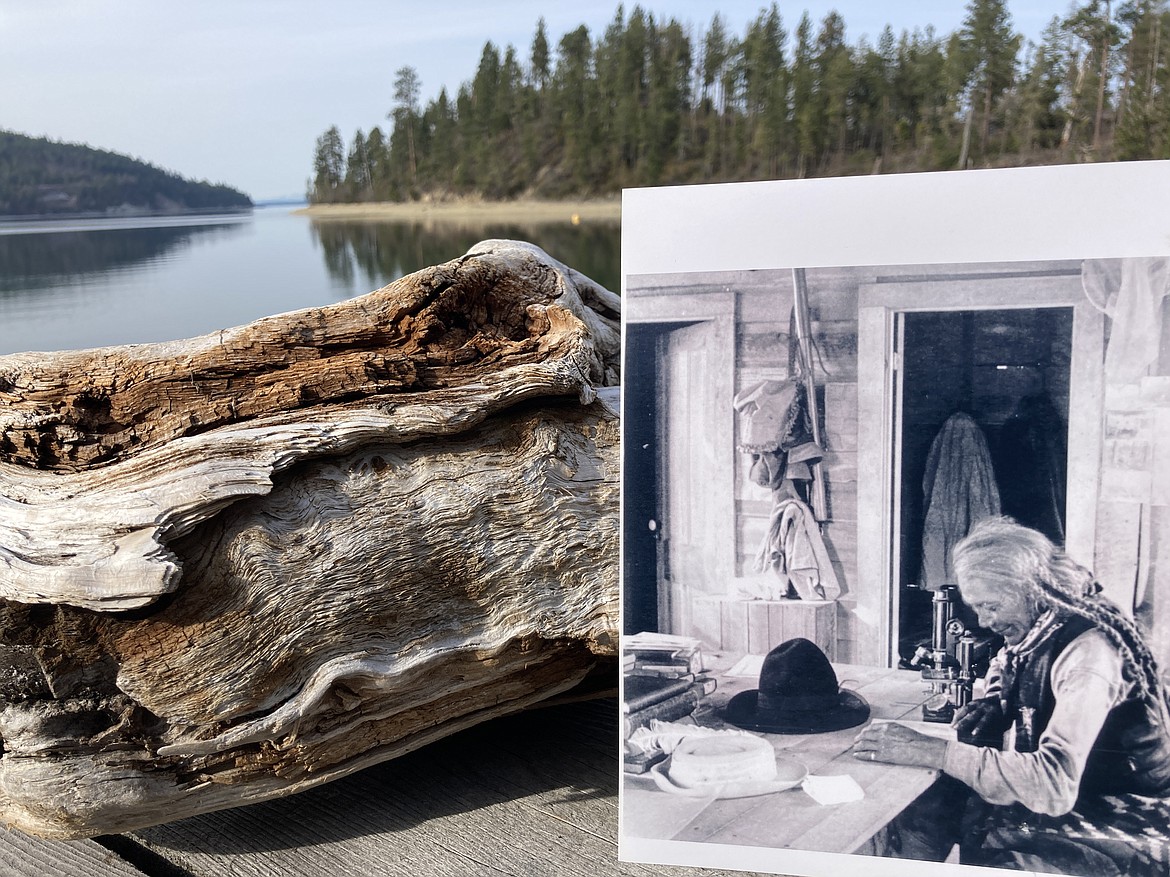

One of the most prominent educators of early UM scientists was Lassaw Red Horn. A revered elder of the Ql̓ispé (Pend d'Oreille) tribe, in the early 1900s Red Horn provided critical information to Bio Station researchers about regional plants and animals and their medicinal and cultural uses. Red Horn was highly respected and appreciated by FLBS scientists for his generous sharing of his extensive knowledge, particularly his knowledge of Flathead Lake, and he was often invited to FLBS to consult on scientific studies.

In fact, Red Horn’s impact on Montana science, culture, and history is so great that Montana State University’s Museum of the Rockies—which is world-renowned for its vast collection of one-of-a-kind dinosaur fossils—considers a shirt worn by Red Horn to be among its most treasured items.

Today, the relationship between the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) and FLBS carries on, as CSKT researchers frequently work side by side with FLBS scientists. This modern collaborative effort to understand and protect the ecosystems of the Flathead includes conducting Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) monitoring and, most recently, a joint research project investigating mercury levels in the fishes of Flathead Lake.

Just yesterday, educators representing CSKT, the Flathead Lakers, Montana State Parks, and the Bio Station led a learning event about invasive mussels for Bigfork Middle School students at Wayfarers State Park. Known as a Mussel Walk, these events were first started by CSKT educators nearly a decade ago to give future generations the understanding and tools to respect and help protect this pristine watershed that sustains and supports our ecosystems, communities, and economies. Another Mussel Walk is happening today—perhaps at this very moment—with Polson Middle School students at Polson’s Salish Point.

Believing you have all the answers can be an intoxicating curse (see Exhibit A: Me, as I write this column). But while my condition may be incurable, I try my best to push against it every day. In my nearly 40 years on this planet, I am growing to realize that the best way for me to make a positive impact on any environment is to swallow my immediate opinions and humbly, respectfully, learn from those who have been there before.

Over 100 years ago, Lassaw Red Horn and so many others like him had the generosity to share intimate knowledge of this ecosystem. This began a legacy of education that continues to this day, a storied tradition deserving of our utmost appreciation, responsibility, and respect. Learning is a lifelong adventure, after all, and every adventure is more exhilarating when everyone is along for the ride.

Now, if you’ll excuse me: Spring is in the air. The days are (finally) getting warmer, and my time for editorializing this month is at an end. If you need me, I’ll be in Polson, quietly observing a Mussel Walk, doing my best to learn something new. Something that I will inevitably pass on to my daughters in the hopes that they might someday help build a better tomorrow in this Last, Best Place that we call home—assuming, of course, that I can get them to stop singing about baby sharks long enough to listen to what I have to say.