“Photography is 90 percent man, 10 percent equipment”: A quick peek into the life of Herman Schnitzmeyer

If there was ever an article that I wish I could “write” in pictures alone, this would be the one. Herman Schnitzmeyer didn’t venture too far past the Narrows on Flathead Lake, which is unfortunate for those of us in Bigfork, but when looking at his overall body of work and what he captured during the early 20th century here in western Montana, one can still appreciate what he did record for our little corner of the world. Once all but forgotten, Schnitzmeyer has re-emerged as one of the preeminent early photographers in Montana thanks in no small part to local historians like Paul Fugleburg and Denny Kellogg. And while we have to be brief for this article, it is important to note that even trying to winnow this down was tricky, but an attempt was made, nonetheless.

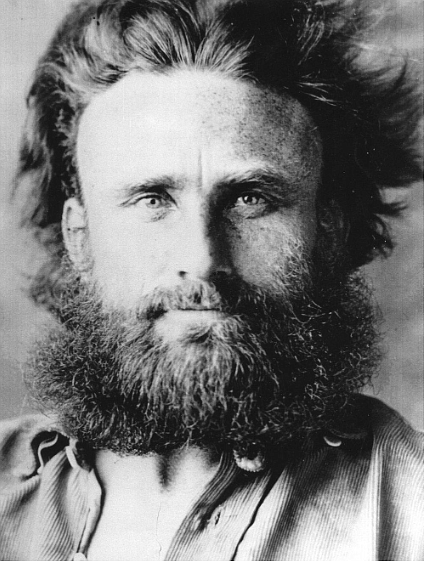

Born in 1880 in Illinois, Schnitzmeyer held a handful of job before becoming a commercial photographer for several years. But when he came to the Flathead in 1910, it wasn’t to start a studio, it was to homestead. He had obtained a claim on Wild Horse Island and arrived to make his mark. His most committed effort was the winter of 1913-1914 when he spent nearly the entire winter on the island. That time alone allowed him to work on his philosophical writings and internal polemics which we can’t cover here but perhaps another day. After those first couple of years, however, he sold his claim of 160 acres and moved into Polson where he went back to what he knew best, taking pictures, of which no subject was to menial. Families, mountains, the indigenous Salish and Kootenai people, steamboats, school portraits, parties, and landmarks were all covered.

He captured the first float plane to land and take off from Flathead Lake on July 27th and 28th, 1913 when Terah T. Maroney, after assembling his airplane in Polson, took to the skies, making several laps around the steamboat Klondyke. Schnitzmeyer pursued a solid mix of studio and Plein air work as it were. He kept no set schedule per se so interested people would usually just have to show up and hope he was in to take their pictures. Getting those pictures was also another matter, as sometimes they might be ready promptly, while other times you might be waiting a while. His pictures were worth the wait. Bill Gregg, who chauffeured Schnitzmeyer around on his photographic excursions for many years, also relayed a story that while they often packed lunches for their trips, if the mood, and his stomach, struck him, Schnitzmeyer would find his next vista close to a farmhouse which, after getting his shot, he would then approach and ask the residents if he could buy dinner for him and his chauffer. Truly a man of the people. After roughly 7 years in Polson, Schnitzmeyer sold his studio to apprentice Julius Meiers and continued his primary photographic work for the Northern Pacific railroad.

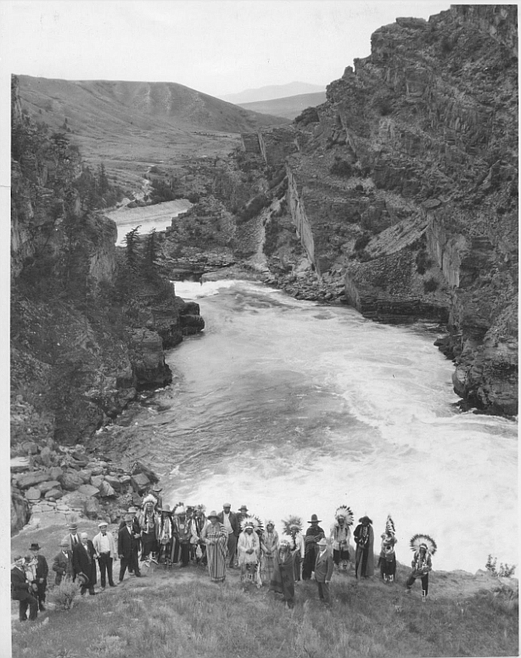

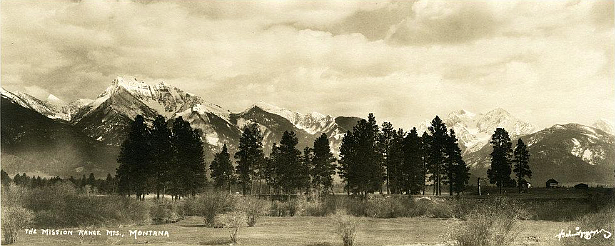

The Northern Pacific years were a boon for Schnitzmeyer. He traveled extensively in the Pacific northwest capturing scenes to be used for the railroads promotional department. It was a job he excelled at. In 1930, Schnitzmeyer made an excursion back to Polson, this time to capture the dedication of the site that would eventually become Kerr, now Seli’š Ksanka Qlispe’ Dam, to the south of Polson. These are truly some of his most powerful images in my opinion. Something that some people might have seen as just another dam site dedication, but the contrast and symbolism are powerful. Overall, by 1930, however, the tenure with the Northern Pacific had runs its course and Herman had moved to Missoula. While there, Schnitzmeyer dabbled in lecturing at the University of Montana as well as teaching photography. A lifelong bachelor Schnitzmeyer eventually passed away as a recluse with nothing to his name on September 2, 1939.

One cannot truly describe, in a few paragraphs, the photographic legacy that Schnitzmeyer created. He laid bare the transition from still a relatively sleepy agrarian Mission Valley and Flathead Lake to a “modern” one. His juxtapositions showing the old and new, the young and old, machines and nature are sometimes subtle but often not that subtle. It makes one almost wonder if he was playing a joke on future generations showing us just how stark some of the shifts taking place in society and the country at that time were. Lucky for us, he lugged that camera around and captured those changes, especially in and around the Flathead, so that we can all appreciate what life was like in Montana over 100 years ago.